Rev. Jared Buss

Pittsburgh New Church; March 24, 2024

Readings: Matt. 21:14-16; Zech. 9:9, 16 (children’s talk); TCR §114; AC §8455

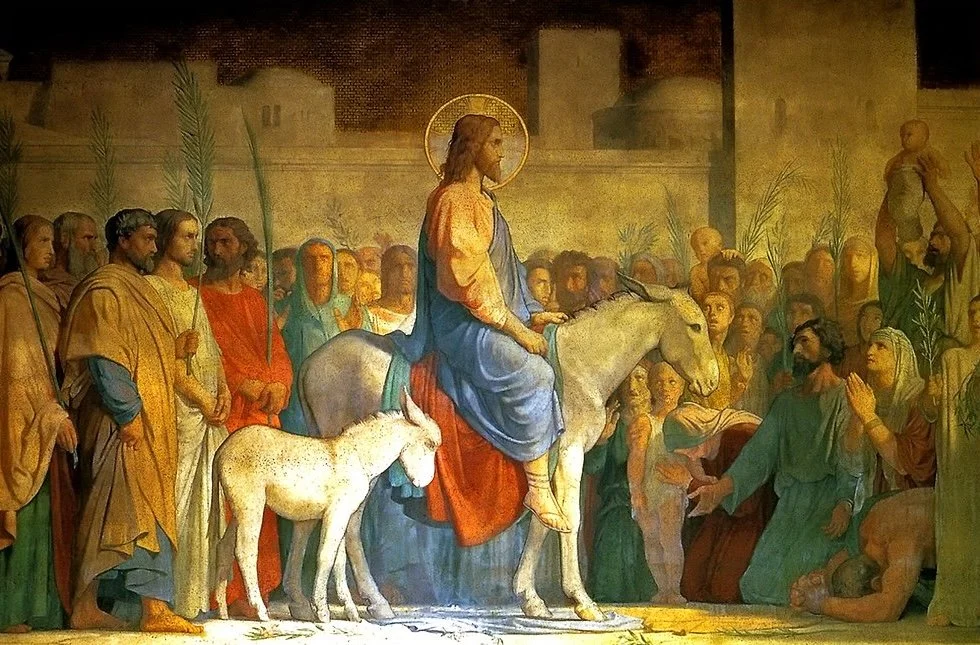

In this portion of the service we’re going to explore who the Lord really is—and we’re especially going to explore what He values most of all. The idea we’re starting with is the idea that He is a king. That’s how He was hailed when He rode into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday.

The Word makes it clear that He is a king. But it’s also pretty clear that that, throughout most of His ministry on earth, He didn’t seem like a king. He didn’t dress like a king; He didn’t wear a crown. People looked at Him and said things like, “Is this not the carpenter’s son?” (Matt. 13:55). He had no courtiers, no palace; in fact He said, “Foxes have holes and birds of the air have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay His head” (Matt. 8:20). He was a wanderer. In Isaiah there’s a prophecy of His coming that reads, “He has no form or comeliness; and when we see Him, there is no beauty that we should desire Him” (53:2). Why did He present Himself this way, if He really was the king of heaven and earth?

One answer is that His kingdom is not of this world (John 18:36). The Lord was not an earthly king—so He didn’t surround Himself with earthly trappings of royalty. The book of Revelation portrays Him as He’s seen in heaven—and in heaven’s light He looks very much like a king (e.g. 19:11-16).

But there is another answer, which is that the Lord is more than a king. He wants us to see Him as something more than our king. All power in heaven and on earth is His (Matt. 28:18). He exemplifies the qualities that kings are supposed to have—majesty, glory and wisdom. It would be wrong to take any of these away from Him. But He is more than these things. He wants us to see more than these qualities in Him.

We’ll turn, now, to the first of our readings from the Heavenly Doctrine of the New Church, which is from a book called True Christian Religion. We read: [§114].

The two qualities that make up the essence of God are love and wisdom (TCR §37ff; DLW §28ff). These two qualities can’t actually be separated—they define each other, and they depend on each other (TCR §41; DLW §§14-16, 34-39). But we can make a distinction between God’s love and His wisdom (see DLW §14). Because He is these two things, many of His names come in pairs: He is the Lord God. He is Jesus Christ. And because He is these two things, He has two functions—or you could say, two primary roles. His kingly function, which is what we’ve been discussing so far, is the ministry of His truth. His other function is a priestly function, which is the ministry of His love.

Like I said, the Lord’s love and His wisdom—or His goodness and His truth—can’t actually be separated. When He acts as a king, or when He is in His kingly function, He isn’t acting from truth alone. He rules by means of truth from good (cf. AC §3009). And when He is in His priestly function, He doesn’t act from love alone: His love expresses itself through wisdom. Even so, these two roles are distinct, especially from our perspective. Sometimes we see the Lord as a king; other times we see Him as a priest, or a healer, or a savior. It’s hard for our merely human brains to hold onto everything that He is at once. We tend to focus on one or another of His aspects. Sometimes we want to see His power. Other times we want to feel His love.

There is absolutely nothing wrong with wanting the Lord to be our king—with wanting to be part of a kingdom that He rules with wisdom and with grace. But if one of His two functions is nearer to His heart, it’s the priestly function—the ministry of love. His love and His wisdom can’t really be separated, but there is a sense in which His love comes first. Wisdom comes from love. Love is His soul, and wisdom is the body from that soul (cf. DLW §14). Think of it this way: the Lord is called both Jesus and Christ. The name “Christ,” which means “Anointed,” has to do with His kingly function, and the name “Jesus,” which means “Savior,” has to do with His priestly function. They’re both His names, but Jesus is His first name. And when you’re with your own people, you want to be known by your first name.

The reason why all of this matters is that it helps us keep our eye on what the Lord wants for us most of all. His truth is beautiful. The kingdom that He rules is a kingdom of peace, and that peace is better than anything that this world can give us. Yet there is another quality that is even closer to the heart of all things, and the Lord wants to share it with us.

Our next reading is also from the Heavenly Doctrine, this time from the book Arcana Coelestia or Secrets of Heaven. This reading describes the quality of the truth that fills the kingdom of heaven. This truth is called the truth of peace. We read: [§8455].

The state of mind that’s described in this passage is beautiful. The truth of peace fills the kingdom of God like daybreak fills the earth. What’s revealed in that light is that God holds all things in His hands: He governs all things, and provides all things, and leads towards an end that is good. When we believe these things—when we have confidence in the Lord—then nothing that tomorrow holds can disturb us. Who doesn’t long for peace that deep? And yet, this peace is not the very heart of the Lord’s kingdom. It comes from something else. As the reading says, it depends on love to the Lord.

In the Heavenly Doctrine we’re told that there are two inmost things of heaven: innocence and peace (HH §285; ML §394). And if one of these comes first, it’s innocence. Just as love is interior to wisdom, innocence is interior to peace (cf. D. Wis. 3). Innocence is the source of peace (cf. HH §285; ML §394). These qualities fill the heavens because the spirit of the Lord fills the heavens—and He is innocence itself, just as He is peace itself. This is why, in Isaiah, He’s called the Prince of Peace, and in the same verse is also said to be the child that is born to us. (9:6; cf. AC §430).

This is why He’s called the Lamb. When John the Baptist saw the Lord, He said: “Behold! The Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world!” (1:29, cf. v. 36). Lambs are symbols for innocence. Lambs are soft and gentle. They’re also the young of their species; and in youth—or childhood—we see a reflection of the innocence of heaven, which is the Lord’s innocence (cf. AC §§2305, 2306; HH §§277, 341).

The Lord is many things, but it seems that innocence is the inmost of them all. In the book Heaven and Hell we read:

Because innocence is the very being of good with the angels of heaven, it is evident that the Divine Good that goes forth from the Lord is innocence itself, for it is that good that flows into angels, and affects their inmosts, and aligns and adapts them to receive all the good of heaven. (§282)

It is in innocence that God dwells with us. Innocence is what He wants to share with us.

And what is innocence? In everyday speech, the word means guiltlessness, or blamelessness—if you’re innocent that means you’ve done nothing wrong. This is an aspect of heavenly innocence. God is the only person who has never done anything wrong—but He can bring us into a state of innocence, a state in which the bad things we’ve done are so far removed from us that they cast no shadows on our minds.

But heavenly innocence is more than just guiltlessness. Little children (in their good moments) show us what this innocence is like. Their innocence is tender—and it’s playful (cf. HH §§281, 288; AE §996.2). The Lord wants us to see these qualities in Him.

The closest thing to a definition of innocence that we’re given in the Heavenly Doctrine is that it’s a willingness to be led by the Lord (HH §§281, 341; cf. §§278, 280; ML §414). We’re told that the highest and wisest angels are also the most innocent, “for more than all others they love to be led by the Lord as little children by their father” (HH §280; cf. AE §996.2). Innocence is a total trust in the Lord. It’s the state of simply rejoicing to go where He leads us.

Of course, it doesn’t work to define innocence as a willingness to be led by the Lord when we’re talking about the Lord. He is innocence itself—does this mean that He loves to be led by Himself? That doesn’t make sense. It sounds self-oriented, and the Lord is anything but self-oriented. In human beings, innocence is a willingness to be led by the Lord. In the Lord, innocence is the reciprocal willingness: a willingness to lead us. To lead us to every good thing is His joy.

Innocence isn’t always something that we value very much. We don’t always think of it as something that we need. In some states of mind, we see it as worthless: we associate it with naïveté, and treat it with contempt. For these reasons, God doesn’t always appear to us as the God of innocence. Sometimes that isn’t the God we need. Sometimes we need the Lord to be a hero who will deliver us from evil; sometimes we need Him to be an authority figure. He is all of these things. He has many names, and all of them are good.

In the Gospel we see that He fills many roles. On Palm Sunday He was received as a king—and He is a king. But He has another aspect, an aspect in which He’s much closer than a king. He reveals it to us softly. You can’t make someone value innocence by hitting them over the head with it. But if we want to see His innocence, it’s there. We see it in the stories in which He takes little children into His arms and blesses them (Mark 9:36, 10:16, et al.). We hear it whenever He talks about what He really wants—when He says, “Father, I desire that they also whom You gave Me may be with Me where I am” (John 17:24). We hear it when He says, “the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give His life a ransom for many.” (Matt. 20:28)

Amen.